Careers outside academia - data science

We all know academia is a bit of a pyramid scheme. Far more PhD students graduate each year than can possibly become professors. Students often ask for ideas of what they could do outside of academia. However, academics are often the worst people to ask, because we’re stuck inside the system. Recently, when I’ve asked people for ideas of what my students could do post graduation, they’ve said “data science”. But what is data science? And what kinds of things do people do in data science? In this blog post I’m going to try and summarise what I learnt about data science from attending the EARL - Enterprise Applications of the R Language conference last week in London.

We all know academia is a bit of a pyramid scheme. Far more PhD students graduate each year than can possibly become professors. Students often ask for ideas of what they could do outside of academia. However, academics are often the worst people to ask, because we’re stuck inside the system. Recently, when I’ve asked people for ideas of what my students could do post graduation, they’ve said “data science”. But what is data science? And what kinds of things do people do in data science? In this blog post I’m going to try and summarise what I learnt about data science from attending the EARL - Enterprise Applications of the R Language conference last week in London.

TL;DR: I think quantitative biologists have the skills to make excellent data scientists.

Disclaimer: These are my opinions, and my interpretation of what I saw and heard during the conference. Some of this came from the talks and my general impressions, other information came from discussions I had with people during the breaks. Apologies to data scientists if you feel I have misrepresented any of your opinions and/or misinterpreted what you were saying. Also I feel like there is quite a lot of disagreement about some of this, so again apologies if you feel my interpretation is incorrect.

2017-09-26: Post updated with comments from Tim Lucas (@statsforbios). See below.

R we impostors?

I started the EARL meeting feeling very intimidated and full of impostor syndrome. People I chatted to in the breaks seemed confused as to why I was there, and I doubted whether my R skills were really up to the meeting standard. However, as the meeting went on I realised that this wasn’t the case at all. Most speakers were doing really similar things to what we do as biologists who use R a lot, especially those of us using other people’s data, and/or needing to wrangle multiple datasets to make sense of a problem. Near the end I attended several talks on reproducibility where people were discussing the exact same problems, and the exact same solutions and workflows, that we have been using. And when people talked about statistics, I realised that quantitative ecologists are way ahead here! This led to me to realise that many of us have the skills to be data scientists we just need to know how to package them for non academic employers.

What is data science? What do data scientists do?

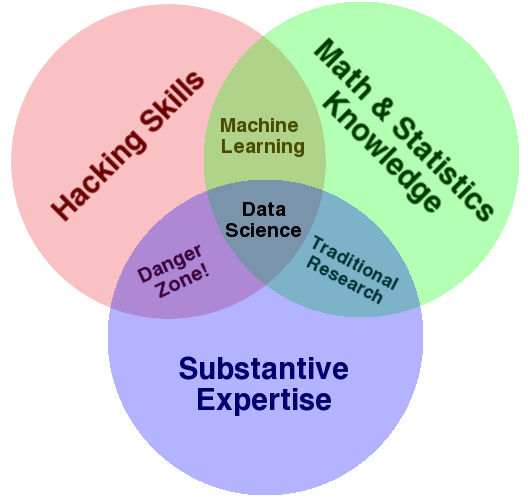

Who knows! There seems to be a lot of debate about what a data scientist really is, and how they differ from statisticians and data analysts. The Venn diagram below gets thrown about a lot, but I’m not sure it really helps that much! It seems people (sort of) agree that data scientists “extract information from data”. Not very specific. It also feels like a buzzword, and many “data scientists” rebel against the term for that reason.

To summarise the process (from what I gathered listening to people at the meeting), a basic data science project works as follows: a client gives you some data and asks you to do something with it. This could be a very specific task, such as predicting when a client might leave an investment bank, or might be very general, for example looking at many year’s worth of data and trying to spot patterns that might then lead to questions. Generally people seemed to work very closely with their clients, discussing in great detail what was required and reporting back frequently. A lot of work seemed to involve the initial data cleaning and wrangling, and projects needed to change to fit with the changing needs of the client. As a final product, clients wanted a variety of things. Some required reports, others software, and many wanted some kind of application or dashboard that would allow them to run analyses themselves.

How does this relate to what we do in PhDs/postdocs?

I’ve noted a number of similarities and differences below.

Similarities

- Data are extremely messy, and lots of data wrangling is needed. Yeah we’ve got this one covered in biology!

- Statistics used are standard statistics used in biology - linear models, GLMs, clustering. In fact most PhDs use more complex stats. Use this to your advantage!

- Ability to communicate what you did and why, and what you found, is key. The only difference is the audience may need more help understanding some concepts, particularly as regards to uncertainty in models.

- Data visualisation is really important.

- Presentation skills are really important.

Differences

- Lots of emphasis on data exploration to come up with questions, rather than a priori hypotheses, although we sometimes do that in biology too.

- Data are always “other people’s data”, though you can ask clients to provide/collect other pertinent data. This means you have to work hard to understand it.

- Privacy and data protection are likely to be an issue, so learn how to deal with this and be prepared to work around issues where you can’t ever see the actual data, just a dummy subset.

- Often multiple people are involved in a single project. So rather than running all the analyses for a project, you might just run one analysis that makes up a bigger whole.

- Often clients wanted to predict what would happen the future, which we don’t do that often.

Dealing with perception bias

One thing to be aware of is that there are misconceptions among employers about academics. I had a long chat with someone who claimed that employers thought PhDs/postdocs made poor data scientists because (1) they couldn’t cope with messy data; (2) they couldn’t use databases; (3) they couldn’t deal with working 9-5; and (4) they didn’t know how to monetise their skills or deal with clients.

Of course biologists often have the messiest data and spend huge amounts of time data wrangling, many people use databases, and academics often work far longer than eight hour days, even if not exactly 9-5! However, it’s worth trying to make this kind of thing clear in your job applications and CV, and writing your experience in a way that will sell the relevance of your PhD work to the job. The issue of dealing with knowing how to deal with clients is more true, but this is something that can be taught, and “work experience” (see below) may help convince employers that you have the ability to do this.

I got annoyed in a talk where someone referred to scientists as “citizen data scientists” because we vaguely know what we are doing. In the questions someone said we were a hopeless case because we would never let go of our “point and click” mentality. So these are the kinds of people we are trying to convince that we are actually pretty competent!

Recommendations for making yourself more employable in data science (using R)

Finally I’ll summarise some of the advice people gave me at the meeting for making yourself more employable. Again, take these with a pinch of salt as I’m sure it varies across employers. But it might give you some ideas. I also recommend asking around on something like Twitter if you’re interested in pursuing data science. There is a really friendly community out there who I’m sure can give better and more up-to-date advice! But here’s what I picked up on…

-

Read and digest Hadley Wickham’s R For Data Science book . Virtually all you need to know in R for data science is there!

-

Stay on top of new stuff in R. Although many people were using base R, there was a general leaning towards the

tidyversepackages, and people were using up-to-date versions of these. Keeping an eye on new R advances via #rstats on Twitter or similar seems like a good plan. -

Learn Shiny. Everyone seemed to have a Shiny app for their clients, or some kind of dashboard. Learn how to do this!

-

Make R packages. You don’t need to release them on CRAN, just make them to keep your analyses for each paper in a tidy format. Employers love to see that you can make R packages.

-

Learn about reproducibility. This is as big a buzzword in data science as it is in science these days. Get down with the cool kids and get reproducible. Check out papers here: https://peerj.com/collections/50-practicaldatascistats/

-

Tailor your CV to make sure you emphasise the skills employers need. And make sure to address common areas of perception bias here. Also emphasise the skills you have that make you better than the usual data science direct entrant - you’ve had extensive experience with messy data, complex stats

-

Learn machine learning. This also seems to be a popular skill required in a lot of data science jobs. But again this will change as the fashionable methods change, so keep an eye on what is “hot” at the point you think of applying for jobs.

-

Learn SQL, and use databases. Most companies will store their data in some kind of database, so knowing how to extract data from a database is key. SQL is not hard, and packages like

dbplyrwhich is part of thetidyversemake extracting data from databases pretty straightforward. According to one person I spoke to, many PhDs do not have this experience, as their data are often in spreadsheets or text files. -

Work experience. One person I spoke to said that there was no way a recent PhD/postdoc would get a job in data science without work experience. It used to be common, but is becoming more competitive as more undergraduate degrees train people in the area. I am unsure that this is true of every company, and certain jobs would seem to benefit from domain specific ecology knowledge more than others. But this tip was pretty depressing, as it’s not easy or economically viable for many of us to just go out and volunteer or take on an unpaid internship to get experience. However, there are some options. First, sharing code etc. via GitHub (or similar) is a good way to showcase your code and your talents. Second, if you can spare the time, you could take on some projects for others to create a “portfolio” of your skills. For example, if people have datasets lying around, you could volunteer to analyse these for them, produce a nice Rmarkdown report and/or Shiny app, and publish it all on GitHub for the world to see. Think of GitHub (or similar) as your portfolio. Sadly this will take up some of your free time, but you’ll probably also get authorship on any papers, and can demonstrate that you got a task from a “client” and created an “output” in a timely manner.

Hope some of this is helpful or interesting!

Natalie

@nhcooper123

Picture credit: Noam Ross, Drew Conway.

Further comments by Tim Lucas (@statsforbios)

I had a bunch of thoughts about this post and after tweeting them, Natalie suggested I add them to the blog post. While the quote “academics are often the worst people to ask, because we’re stuck inside the system” describes me, I have spent a lot of time thinking about a data-science-esque career path if academia didn’t/doesn’t work out. To that end, I’ve read many job descriptions for analysis/statistics/data science type jobs. I’ve also attended a bunch of LondonR meetings. So hopefully I have some vaguely useful insights.

First some quick generalities. Some job websites have tags for jobs that require R. There’s currently hundreds of jobs being advertised. There’s a skill shortage in this area.

Also, I think it’s silly that physics graduate students are considered to be quantitative and employable in a way biology graduates currently aren’t. A few tweaks to biology undergraduate curricula (bit more R, bit more explicit data munging, basics of machine learning) and biology grads could so easily be the go-to source for data science jobs. But, this post was more about biology PhD students, so I’ll get off my hobby-horse.

- “Most PhDs use more complex stats.”

In particular scientists often handle autocorrelation in space/time/phylogeny or by group (i.e. mixed-effects glms). However, many grad-students are comfortable with autocorrelation due to one of these variables. If you can understand that the same concepts apply to different forms of autocorrelation, your niche “phylogenetic regression” knowledge, that doesn’t feel like it applies to other areas of data science suddenly becomes general.

Secondly, many scientists are mostly interested in autocorrelation because they want unbiased estimates of fixed effects. Therefore the goal is to control for the autocorrelation and then broadly ignore it. However, autocorrelation is also incredibly useful for getting better predictions; which is a more common goal in business data science. This blog post, and others linked within, are a great discussion of the different aims of statistics. So, if you can understand how autocorrelation can be used to improve predictions, by including random-effects in your model, you have realigned yourself with business, without learning how new types of analysis.

- “Learn machine learning. Fashionable methods change”

This is easier than it sounds. There are a few umbrella concepts in machine learning (cross-validation, over-fitting, hyperparameters) that might be new to an ecologist. But the concepts are not terrible difficult compared to the statistics you probably already know. Again see the Dynamic Ecology blog posts. Alternatively the documentation for the R package caret is basically a good intro to machine learning.

From the practical point of view, caret makes machine learning not much harder than GLMs. Two lines of code will tune and fit a machine learning model. Changing one argument will tune and fit an entirely different model. So once you have learned the syntax for random forests (for example) you get neural networks and a million other models for free. Furthermore, the package is always being updated. So you can stay acceptably up-to-date with no additional work.

- “Learn SQL, and use databases.”

I found that database software can be a pain (but maybe that’s just me). But you can learn the concepts of databases and learn to use SQL with dplyr then sqldf in R. The dplyr verbs select, filter and join map directly to database concepts. dplyr is just a generally useful package to know (see section Stay on top of new stuff in R.) so this isn’t just learning for the sake of your CV. After that the package sqldf literally takes a string of SQL and applies it to the dataframes in your R session. While sitting down and learning the SQL syntax is possibly learning for the sake of learning, this again is a small, incremental step (there’s only about 10 commands to learn).

- “Work experience” I can’t guarantee anything, but I have heard that employers look for kaggle or drivendata competition results. These are only data science competitions. You get given some data and are asked to predict the answers to a test dataset. There are leaderboards and (often) busy forums that can help get you going quickly. There are interesting science competitions if that helps motivate you.

So, I think for many biology PhD students, understanding a few new concepts and how some other concepts relate, and replacing lm() with caret::train() in a few scripts could really put you in a great position for applying to data science jobs.

That’s all I got.

Tim Lucas

@statsforbios

APPENDIX

One thing that has always puzzled me about data science is what kinds of stuff could you work on, and what kinds of companies hire data scientists? Here’s a list to help!

What kinds of topics are people “data scienc-ing”?

Here is a list of some of the topics I saw people working on at EARL:

- forecasting numbers of cancer patients in the future

- investigating queue waiting times for high performance computing clusters

- helping make government reports reproducible

- predicting profit from investments and behaviours of investors

- using geotagged data

- predicting bat roost presence

- monitoring sewer network performance

- predicting risk of cancer based on various factors

- analysing grain yields and improving energy efficiency

- auditing businesses

- analysing high frequency industrial component failure

- sentiment analysis (how do people feel about a brand)

- predicting car sales

- using open transport data to improve transport networks

- analysing amounts of green space in cities

- visualising brand identities

There were applications in banking, agriculture, food production, utilities, medicine, transport, architecture, car industry, advertising, manufacturing, auditing, government departments, insurance, pharmaceuticals, consulting, computing, NGOs.

There are some more details on some talks in this blog post by David Smith.

What types of companies have data scientists?

Companies I saw represented at EARL (sorry these are UK centric):

- UK Government (many branches)

- Mango Solutions (data science consultants)

- National Audit Office

- Northumbria Water

- Department for Business Energy and Industrial Strategy

- Microsoft

- Ministry of Defense

- Bank of France

- AstraZeneca

- Investec Specialist Bank

- Macmillan Cancer Support

- Pfizer

- Reed.co.uk

- USwitch

- Capital One

- Prudential

- Transport for London

- Telegraph Media Group

- Accenture

- Thames Water

- Bank of England

- ATASS Sports

- Peak

- Royal London

- British Museum

- Department of Education

- Office of National Statistics

- Crisis

- Ofsted

- RStudio

Update July 2019

I was sent this link which might be useful: www.mastersindatascience.org/careers/data-scientist/. It lists what data science is, what it involves and where you can take a course. I’m not involved with this group but said I’d share the link so here you go!